Buses, politics and privatisation

Introduction

In 1970, control of London Transport passed from central government to the Greater London Council (GLC), an elected body with responsibility for the entire Greater London area.

With old debts written off, and promises of targeted long-term investment, LT’s future looked relatively positive. But without the zeal of their predecessors, LT’s directors saw themselves more as instruments of their political masters’ policies, rather than makers of their own. Opportunities were missed, as passenger numbers continued their decades-long decline, with car ownership rising and congestion increasing.

One option to reduce congestion was to exclude other traffic from designated bus lanes. These started tentatively in 1968 but became more widespread in the early 1970s. This example in Piccadilly Circus opened in 1973.

As control of the GLC changed hands, support for buses ebbed and flowed, and policy became fragmented and inconsistent. Standard off-the-peg one-person-operated buses ill-suited to London conditions were bought to save money. Yet engineers reared on RT and RM buses from AEC had trouble maintaining them, and there were strikes over cuts and job losses.

On the positive side there were advances such as direct radio links between drivers and controllers, and a computerised bus location system that could pinpoint the position of each bus in the fleet. In 1974, Jill Viner became London’s first woman bus driver.

Jill Viner, London’s first woman bus driver, seen here in 1989, three years before the closure of Norbiton garage, where she worked.

As the decade closed London was divided into eight independent bus districts. Though few knew it at the time, this led directly to fundamental changes that we still live with today, enabled by a political row between Margaret Thatcher’s government and the GLC under socialist Ken Livingstone.

The Wandle District established in 1979 covered most of south London, now shared by Arriva and Metrobus.

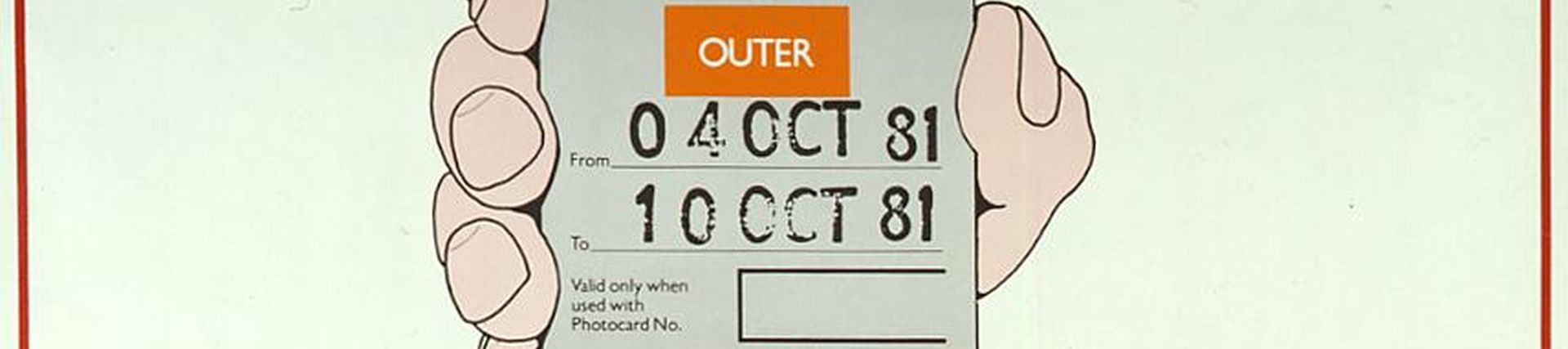

In 1981 Livingstone’s GLC brought in a system of cheaper bus and Tube fares called Fares Fair, funded from local taxes. This ran contrary to the government’s free market thinking and privatisation plans, and the scheme was challenged and deemed illegal by the House of Lords, ultimately leading to the abolition of the GLC altogether.

Returning to government control, LT was renamed London Regional Transport (LRT) in June 1984. While keeping a planning and coordinating role, the new authority was obliged to ‘invite the submission of tenders for certain activities where it is thought appropriate’, rather than providing all services directly.

This 1984 poster encourages bus staff to do their best in the competitive environment they would soon be entering.

Competitive tendering of individual routes started in 1984. This was offered to LRT’s new bus operating company, London Buses Ltd (LBL), and home counties bus operators, but also to chartered coach companies.

By the end of 1986, tendered routes made up almost one eighth of London’s total bus mileage. Almost half the tendered routes were secured by LBL, but only after further cost-cutting, strikes, job losses and garage closures. Subsidiaries of the National Bus Company made up another 40 per cent of the tendered routes, with 15 per cent run by independent operators.

Government funding for LRT was cut by half between 1984 and 1988, making it ‘leaner and fitter’ in the vocabulary of the time. Many departments shrank, merged with others or were closed completely. The GLC was abolished in 1986. Changes in the logistics of bus operations led to the closure of its huge bus overhaul operations at Chiswick and Aldenham. In 1989 LBL reorganised the districts of the late 1970s, which became 11 independent companies, owned and co-ordinated by LRT but competing against each other.

In spring 1989, the new CentreWest company caused controversy by converting two Routemaster routes to high-frequency single deck ‘midibus’ services to cut costs. While some passengers complained, their numbers increased.

A familiar pattern of cost-cutting, job losses and industrial action ensued, as pay rates across the independent companies gradually fell. One operator, London Forest, closed. After this process bottomed out, the companies were sold into the private sector, raising £233 million in 1994-95.

Most of the independent companies were bought by UK bus operators. Four were management buyouts but were sold on in the next few years to bigger concerns. Several of London’s operators are now linked to multinational corporations.

The Harrow Bus Farecard was trialled in 1992-3 and formally launched in February 1995.

The run-up to privatisation coincided with a range of improvements for bus users. Electronic route information similar to the Underground’s dot matrix indicators started to appear at bus stops in 1992. The first low floor buses, with increased accessibility, arrived in 1994 and were given extra impetus by the Disability Discrimination Act of 1995. Trials began for a new contactless stored-payment bus pass using a system developed for ski lifts in Finland, leading directly to the Oyster card in 2003.

It had been a slow and painful process, but bus passenger numbers started to rise for the first time in decades in the late 1990s, setting the scene for dramatic growth in the decade to come.